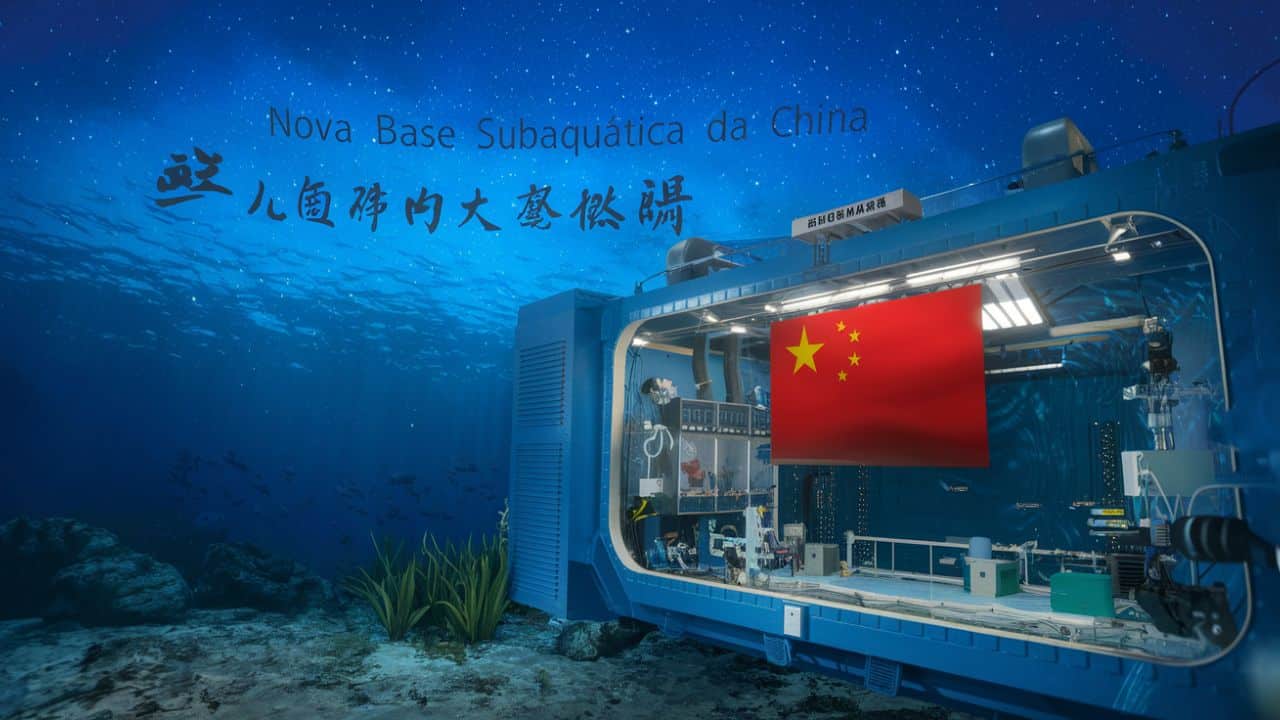

Beijing’s Bold Move to Tap Gas Hydrates Could Reshape Global Power Dynamics

China has confirmed plans to build the world’s first permanent undersea research station to extract gas hydrates—an energy source potentially more powerful than Persian Gulf oil. Scheduled to be operational by 2030, the station will be located in the methane-rich cold seep zones of the South China Sea, enabling six researchers to conduct 45-day missions on the ocean floor.

The gas hydrate reserves in the region are estimated at 80 billion tonnes of oil-equivalent energy, significantly more than the 50 billion tonnes in the Persian Gulf, making it a critical component of China’s long-term energy independence and military strategy.

Energy, Security & Geopolitics Intertwined

While officially labeled a scientific endeavor, the project is a strategic move in the contested South China Sea, where China’s territorial claims under the nine-dash line conflict with Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei. Despite a 2016 ruling by the Permanent Court of Arbitration rejecting China’s claims, Beijing has remained assertive, even as U.S. warships patrol the region under “freedom of navigation” operations.

READ MORE: Samsung Patents Ambitious Quad-Fold Device with Four Panels and Three Hinges

Military Motivation: Fueling the Navy

Methane, a cleaner alternative to coal, could ease China’s reliance on Middle Eastern oil, much of which passes through the vulnerable Strait of Malacca. This shift could enable China’s navy to focus less on protecting distant routes and more on asserting control over nearby strategic waters.

High-Tech Habitat for High-Stakes Research

Equipped with submersibles like Jiaolong and Haima, scientists will use the station to:

- Map undersea cold seeps

- Track methane emissions

- Study marine ecosystems

- Develop safe extraction techniques

Gas hydrates—often called “ice on fire”—can store 160 times their volume in methane. But extraction is risky: missteps can trigger underwater landslides, ocean acidification, or methane leaks, which are 25 times more potent than CO₂ as a greenhouse gas.

A New Energy Race

According to Professor Wang Shuhong of the Chinese Academy of Sciences:

“It’s about guarding the oceans. We hope it will be built soon.”

If China succeeds, it could dominate a new energy era, just as Persian Gulf oil powered U.S. influence in the 20th century. However, failure could expose technical vulnerabilities and invite U.S. counter-moves in the region.

The South China Sea project thus stands at the intersection of science, energy, and geopolitics, signaling a new phase in global power competition.